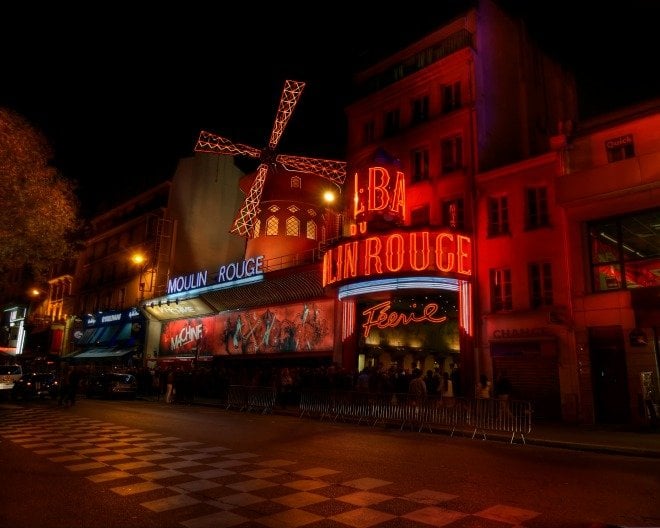

I doubt whether there could be two activities with less in common than grinding flour and performing the can-can, so why on earth is there a windmill sitting on top of the famous Parisian cabaret, Moulin Rouge (meaning Red Windmill)?

Well, the conventional explanation is that Joseph Oller, the man who built the Moulin Rouge in 1889, installed the windmill as a nostalgic nod to a time when Montmartre was a small village situated in open countryside dotted with dozens of windmills– but there’s another, slightly more salacious, explanation of the windmills that may surprise you.

It certainly surprised me. But more on that later.

For now, lets discuss the accepted history of the only two windmills still standing on Montmartre: ‘Le Moulin Blute-Fin’ built in 1604 (corner of Rue Girardon and Rue Lepic), and ‘Le Moulin Radet’ (83 Rue Lepic) built in 1717 and now the site of a charming bistro.

In 1809, a family by the name of Debray, acquired the two windmills– the Blute-Fin was used for separating bran from flour (in French the verb bluter means to sift flour) and the Radet was used to crush onions and spices. Some of these spices – but not the onions, of course – were used to make perfume.

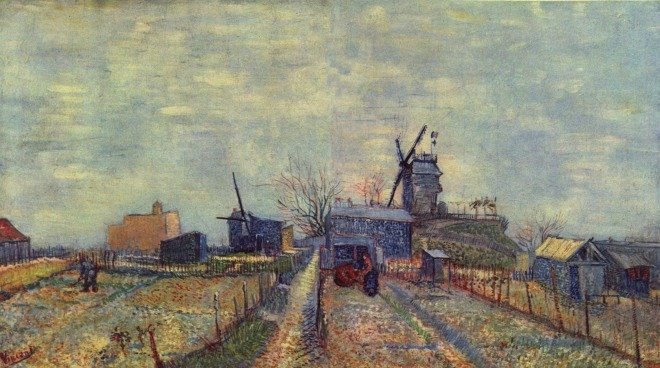

‘Vegetable gardens and the Moulin de Blute-Fin on Montmartre’, 1887, Vincent van Gogh. Copyright © 2015 National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

The two windmills turned happily for a few years until the War of the Sixth Coalition in 1814 (the same war that ended with the abdication of Napolean Bonaparte and his ignominious exile to Elba) when Russian Cossacks stormed Montmartre. (Joseph Bonaparte – brother of the afore-mentioned Napolean – had unfortunately selected to set up his battle headquarters there.)

Fierce fighting ensued during which three Debray men lost their lives…and as if the death of the three men wasn’t tragic enough, the Cossacks then proceeded to nail the body of one of the brothers to the sails of his own windmill– adding you might say, a gruesome spin to the more traditional cross crucifixion.

There remained (sadly) only one Debray brother and he no longer felt suited to the life of hard labor required of a flour miller…and since the rural fields on Montmartre were slowly disappearing and becoming urbanized anyway, he converted his two windmills into a guinguette.

Guinguettes were popular drinking establishments located outside the tax-farmers wall around Paris where alcohol could be consumed nice and cheaply. The word guinguette comes from the name of a local sour white wine, and the term is still used today to describe an open-air refreshment place.

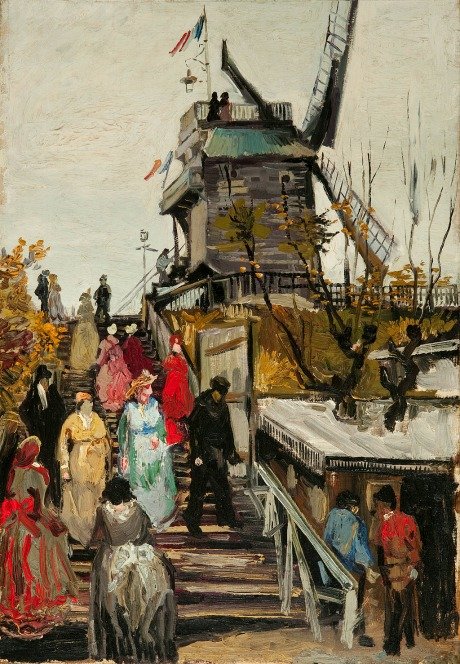

“Le Blute Fin Windmill”, Vincent van Gogh, 1886.

In 1833, the last enterprising Debray brother opened an area for dancing and with the lure of cheap wine and dancing, it’s no surprise that his guinguette was extremely popular, especially on Sundays and public holidays.

It became known as ‘Le Moulin de la Galette’ after a type of bread made with flour from the Debrays mill and sold with a glass of local wine. (Montmartre, rather conveniently, has had vineyards flourishing on its slopes since the Middle Ages.)

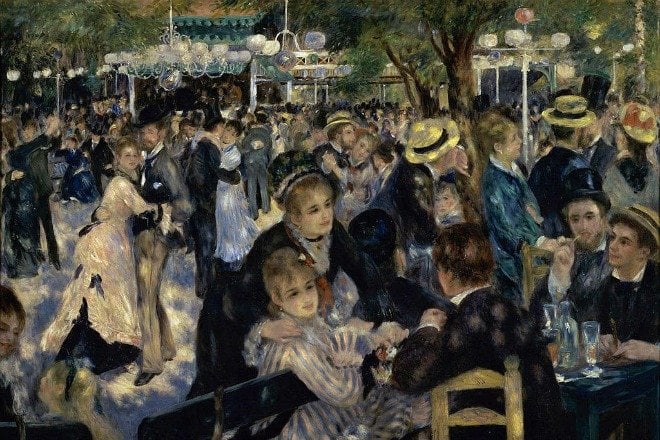

By the end of the 19th century, ‘Le Moulin de la Galette’ was the venue of choice for famous artists like Renoir, Van Gogh, Lautrec and Picasso, who immortalised the guinguette in numerous paintings. (Renoir’s ‘Bal du Moulin de la Galette’ is probably the most famous example.)

The history of these windmills provides a nice respectable explanation for the Moulin Rouge but another explanation involves a red windmill standing above the graves of the three Debray brothers killed defending their mill against the Cossacks. The brothers are buried in the Cimetière de Montmartre and the windmill serves as a fitting memorial for the brothers with the color red symbolizing their shed blood.

The idea is that when Joseph Oller built the Moulin Rouge he erected the red windmill as a (rather dubious) tribute to the three courageous Debray brothers. (I’m sure it’s just a coincidence that the color red also happens to be synonymous with the world’s oldest profession.)

A final explanation is that the area around Montmartre has been a red-light district since the sixteenth century, when the forty-odd windmills dotting the hillside all doubled as brothels. (The millers apparently found it useful to provide their workers with a motivational form of entertainment while they worked.) This interesting form of compensation is apparently the origin of the French phrase ‘entrer comme dans un moulin’ which means to enter a place freely – all were welcome at the windmills!

So you can see now that flour mills and cabarets have a lot more in common than you first thought.

Here is a link to an excellent website showing old photographs and paintings featuring the windmills: Website.

_____________

(Image credits: Mr Jason Hayes, JonathonKhoo, Dave A, Pierre-Auguste Renoir [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, MeganMyers, Vincent Van Gogh [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

[…] Paris Perfect blog post stated that the first windmill in the area was built outside of Paris in the early 1600s. The […]

Been to Paris twice.

Loved it.

My favorite out of all the places we visited.

Lido was also a wonderful cabaret.

However Moulin Rouge was our favorite.

Everyone should visit Paris, it’s a dream place.